Introduction

Optical tweezers is a subject of direct consequence to the advent of the LASER, and now plays a seminal role in single particle physics in statistical mechanics, chemistry and biology. First hints of of the field emerged with the description of radiation pressure by Maxwell, and early experiments by Nichols and Hull (1901) and Lebdev (1901) which showed radiation pressure acting on macroscopic objects using thermal light sources. With the discovery of the LASER, enough optical power was now able to be generated to significantly affect the motion of particles, and led to the discovery of substantial radiation pressure by Arthur Ashkin (1970), and later the invention optical tweezer, which resulted in Ashkin receiving the 2018 Nobel Prize. The manipulation size for optical tweezers is broad, anywhere from singular atoms (nm range) to mammalian cells (m) are considered as viable particles which may become optically trapped (Pesce et al. 2020). This broad range serves well to investigate the limit of quantum mechanics, while also serving applications in particle physics and molecular biology. A key relation to statistical mechanics is the presence of Brownian motion, or the thermal motion of particles. This random, stochastic motion (i.e random walk) opposes the optical force, creating an interplay and series of challenges which will be elaborated upon further in the paper.

Principles of Optical Tweezers

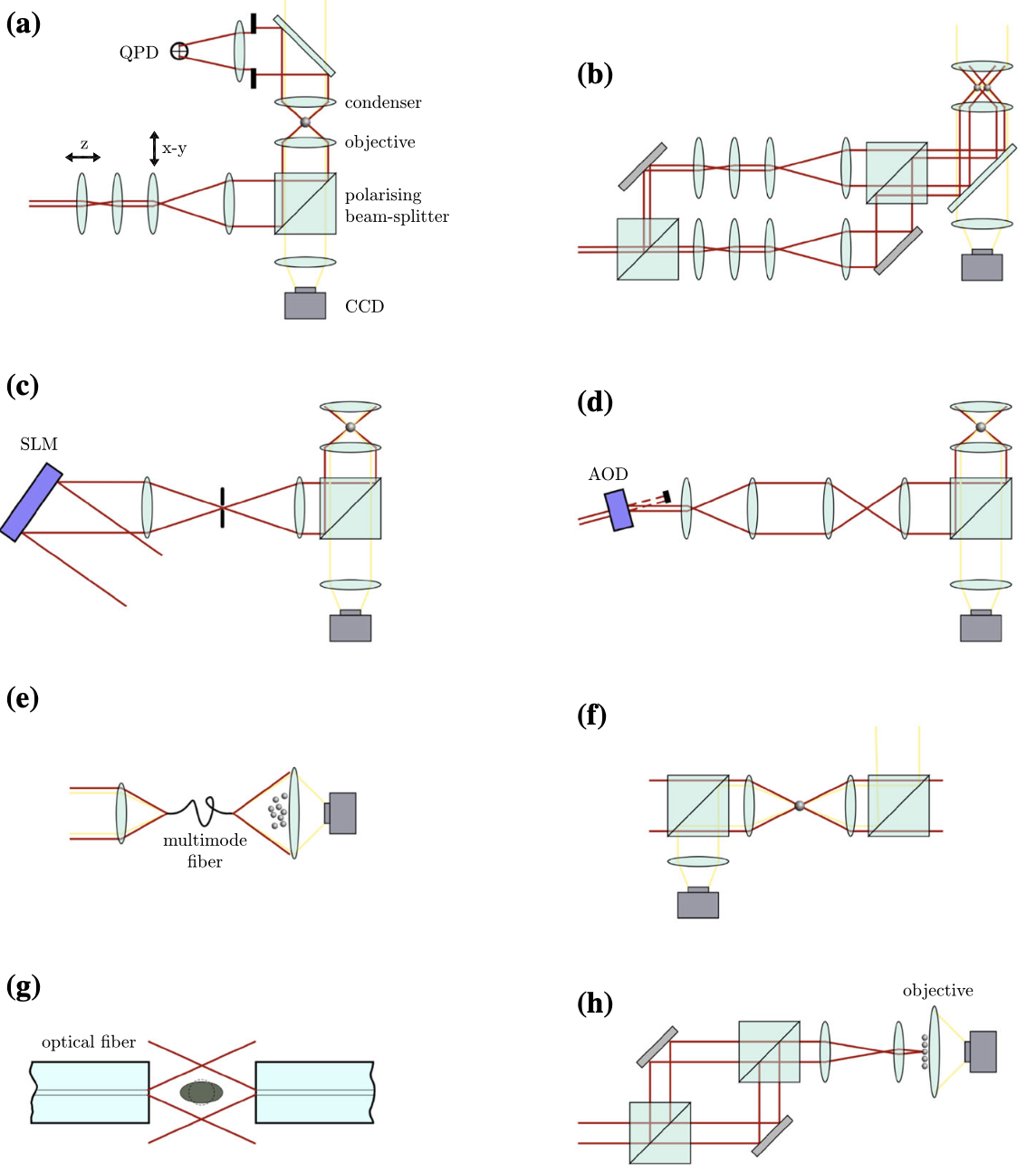

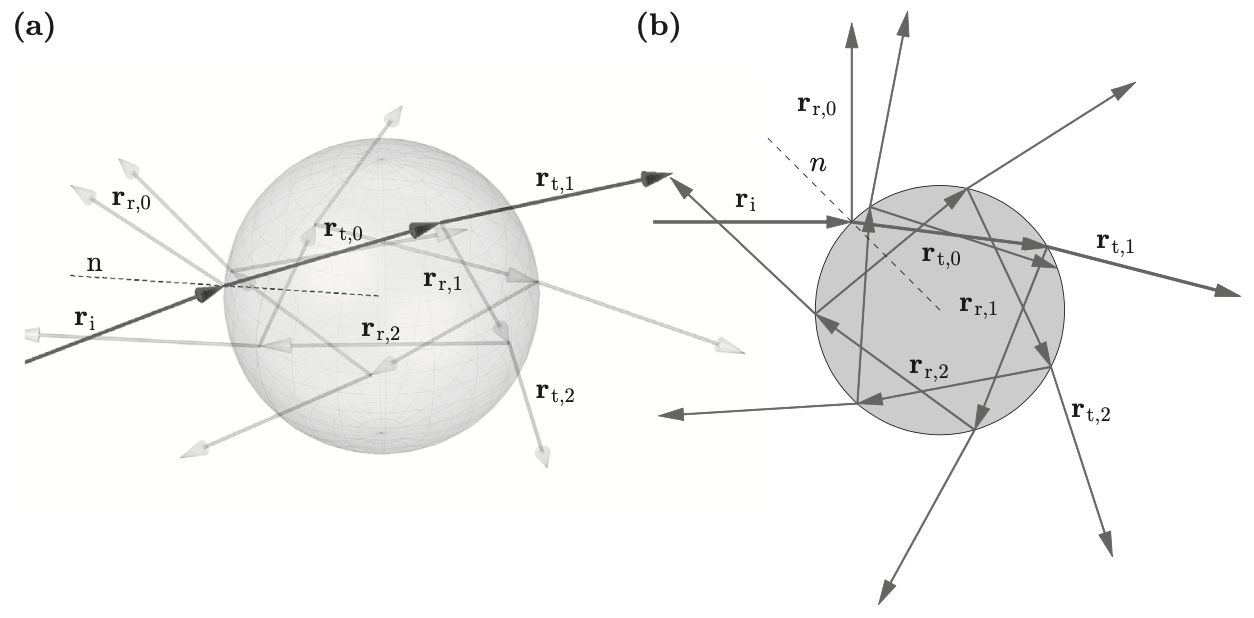

Historically, optical forces have been conceptualized through strong approximations regarding the optical regime (Pesce et al. 2020). The ray-optics regime is such when particle size is much bigger than the optical wavelength, the dipole-approximation regime is when particle size is much smaller. When the particle size is comparable to the optical wavelength, we denote that with intermediate regime. Often, calculations are much simpler under spherical particles, rather than elongated particles, in-homogenous particles, optically anisotropic particles, or complex objects in the size range of tens of nanometers (i.e cells, other biological structures). Thus full Maxwellian calculations must be performed to account for electromagnetic interactions to correctly model optical trapping behaviour in the case of intermediate regime.

We will define important concepts in optical tweezers using notation from Jones et al. (2015). A photon has energy and momentum where is the unit vector in the direction of photons motion. According to Newton’s second law, the maximal recoil force due to a photon, with power P, normally incident on a mirror, as shown in figure 2, is

, where is the unit vector in the direction of propagation. For example, a laser beam of power =3mW gives a force of 1.3E-11N. Though minuscule, in the nanometer scale this force is enough to interact with atoms. The total force acting on a spherical surface due to an incident ray is where , represents direction of the initial incident ray, represents direction of the first reflected ray due to first incident ray, represents all transmitted ray from all subsequent internal reflections, as dictated by snells law. Notice we ignore summation on reflected term, as when is incident on surface, most power is carried by . Since transmission carries most of the power, we can ignore subsequent internal reflections. can be subdivided into the sum of the scattering force, in the direction of the incoming ray and the gradient force, , which is perpendicular to the incoming ray. Multiplying the components of by to construct dimensionless quantities known as the trapping efficiencies: and , where

is the total trapping efficiency. Trapping efficiencies determine how much momentum a photon transfers unto the sphere. It can be shown that grows much faster than as a function of , the angle of incidence, using exact expressions derived by Ashkin (1992). Now having some background in optical tweezers

Brownian Motion

Brownian Motion (BM), as modelled by Langevin Theory, is a classical concept founded upon Newton’s second law and equipartition theorem. Characterized by random collisions that exemplify underlying microscopic fluctuations and interactions between molecules, Brownian motion bridges the gap between the microscopic and macroscopic worlds. Since the discovery by Robert Brown in 1827, and later developments by physicists in the early 20th century, Brownian motion serves as a presage of the convergence of physics and biology, alongside maturate fields like statistics, in regards to stochastic processes especially. Governed by the laws of statistical mechanics (and hence thermodynamics), the study of Brownian motion has helped confirm the existence of the atom, while elucidating the molecular-kinetic concept of heat (Einstein, 1905). BM also helped the study of low-dimensional, deterministic systems giving ostensibly rise to random motion, that is now known to be impossible to solve for (Cecconi et al, 2005)

Haphazardous behaviour shown by particles suspended in a fluid (i.e air, water) are conceptually modelled by random, continuous collisions, displayed mathematically on the microscopic scale by Langevin. Built on initial macroscopic descriptions of Einstein (1905) and Smoluchowski (1906), Langevin’s theory consolidated both random and deterministic components. This section will attempt to illuminate historical foundations of Brownian motion, alongside a brief overview on how Brownian motion resolves statistical mechanics and non-equilibrium fluctuations through Fluctuation Dissipation theorem and linear response theory, finally ending in its relation to optical tweezers through optical trapping.

Einstein

A seminal portion of Einstein’s 1905 work “Investigations on the Theory of Brownian Motion” is showing the diffusion coefficient depends solely on the viscosity of the fluid of the suspended particle, and its size (alongside constants and absolute temperature). And then associating the diffusion coefficient to the mean square displacement of the suspended particles, , subsequently deriving the famous Einstein equation. Here we will show an overview of the derivation. Some simplifying assumptions made in Einsteins paper are: the assumption of ideal gas for the fluid and suspended particles, the fluid particles and suspended particles are spherical, and said species of particles are in thermal equilibrium with each other. First we must deduce osmotic pressure from molecular-kinetic theory of heat. It can be shown free energy is

for intervals () and ()’, assuming movements of single particles are independent of one another to a sufficient degree

hence where is independent of and volume, V. Integrating db over all , then plugging resulting expression into the expression of free-energy we obtain osmotic pressure

where is number of suspended particles, the number of atoms or molecules in one mole of a substance (Avagadros Number) and or number of suspended particles per unit volume. Now we assume spherical shapes, and dynamic equilibrium under a force K in the x direction such that . Under such conditions, we have

through expressions of and we find

from which, assuming particles have radius , fluid viscosity , then the force, , imparts velocity

and diffusion coefficient is -, hence we get

and as a result of diffusion, the number of particles passing through a unit area of unit time is D. From the differential equation of diffusion

where . The free diffusion equation shows how the distribution function evolves. Solving for we find the distribution function to be a Gaussian. On average, the particles will move to areas of less density, diffusion being the cause of the distribution tending to uniformity. From the free diffusion equation we may derive the Focker-Plank equation, which describes how the distribution function evolves in the presence of diffusion and drift. From a change of coordinates and using centre of mass in the free diffusion equation, we may arrive at . This equation shows that the mean value of displacement in the x-direction , evolves with the square root of time. The derivations show a masterful synthesis of early statistical mechanics and molecular-kinetic theory and laid important early work for Brownian motion.

Langevin

The Langevin equations elegantly capture the intricate interplay between the deterministic forces that act upon a particle, such as friction, and the stochastic or random forces that stem from the thermal motion of the surrounding fluid molecules, providing a framework for further analysis on Brownian motion. A translation of Langevin’s 1908 paper by Gythiel and Lemons (1997) is used as reference in this section. Both Einstein and Langevin arrived at the same result, where the root mean square displacement of a Brownian particle evolves with the square-root of time. A formal derivation isn’t shown as the same result was derived above, though the process is as follows: beginning with

where is the viscosity of the fluid, is the radius of the particle, is a complementary force with zero mean = 0 whose magnitude maintains agitation of the particle, moving it around in free space, and is the displacement of the particle. Through solving this differential equation, we may arrive at

for time interval . The over-damped Langevin equation is of particular importance to optical tweezers:

where = and is white noise with intensity 2, where the mean, , is zero.

Linear Response Theory

The Kinetic method approach to non-quilibrium statistical mechanics focuses on the evolution of distribution functions describing the probability of finding particles with certain properties, such as position and momentum, in the phase space of the systems. Though applicable broadly, the kinetic method fails to apply to interacting systems, nor dense systems. To deduce properties of systems characterized by interactions, or higher densities, we need to adopt the Linear Response Theory (LRT). In using the LRT, we are limited to non-equilibrium states near equilibrium. From a basic knowledge of microscopic structure and the dynamics of the system, LRT allows us to calculate the kinetic coefficients and is valid when applied field is small. Since the thermodynamic quantities change proportionally to applied field (again, when its small), it is of interest to find the linear response function, which acts as the proportionality constant and contains pertinent information on the system. At the heart of the theory is the Fluctuation Dissipation theorem, which connects the response of a system to an external perturbation with its internal thermal fluctuations.

Fluctuation Dissipation theorem (FDT), first thought to be introduced by Harry Nyquist, and later proved by Callen and Welton in 1951 who established a connection “between the impedance in a general linear dissipative system and the fluctuations of appropriate generalized forces” (Collen, Welton 1951). This work was later expanded by Kubo’s theory of time-dependent correlation functions. Originally, FDR was thought to hold only for systems that were near thermodynamic equilibrium and Hamiltonian, though it has been shown that the generalized FDR holds for a large class of chaotic systems in natural sciences (Bettolo et al. 2008). The Fluctuation Dissipation Theorem expresses that a mechanism of energy dispersion must be closely related to fluctuations in thermal equilibrium. A famous manifestation of the FDT is the Einstein relation: which relates the diffusion coefficient to the mobility of the particle. In general, as per Kubo (1986) we may write the conductivity formula, which gives an expression for an admittance in relation to the correlation function of fluctuations, as where the bracketed term inside the integral corresponds to correlation function of current.

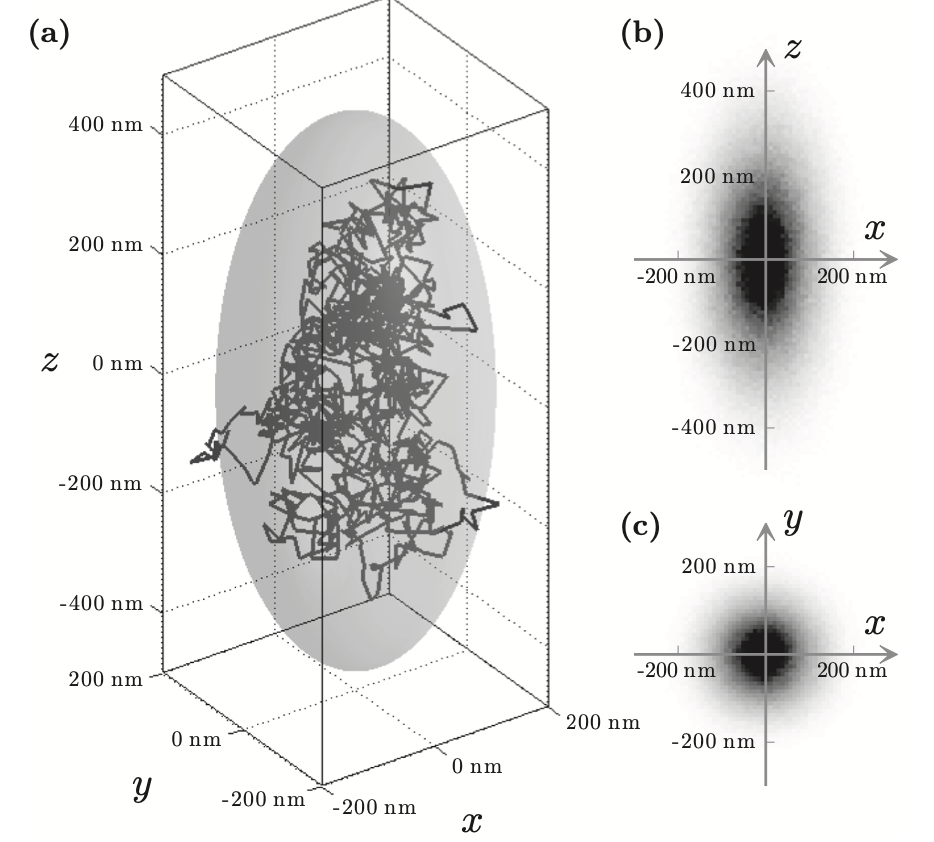

A Brownian particle in an optical trap will experience an interplay of interactions, where the Brownian motion pushes the particle out of the trap, while optical forces drive particle towards the potential minimum. From this, the challenges that Brownian motion present to the study of Optical tweezers, is obvious, as BM challenges the particle out from the optical trap, and increases noise of the system, leaving the particle in a dynamic equilibrium between contrasting forces. The motion of the optically trapped particle may be described, in three dimension, by a set of over-damped Langevin equations with a harmonic restoring force:

where z is the direction of propagation of the beam, the stiffness is described by , , is the particle friction coefficient, and are independent white noises. A corresponding system of finite difference equations can be found. =1.0 fN/nm and =0.2 fN/nm, since trapping stiffness is larger along propagation axis, the particle explores an ellipsoidal volume inside the trap (Pesce et al. 2020).

Conclusion

Optical tweezers is an emergent new field in physics as a result of the invention of the LASER. Though the field won a Nobel in 2018 for physics, optical tweezers have important uses in molecular biology, chemistry, and neuroscience, to name a few. The paper explored the connection to statistical mechanics in particular, especially how optical tweezers relates to the study of Brownian motion, and non-equilibrium statistical mechanics. Brownian motion, a stochastic process, counters the optical force, which is keeping the particle in an optical trap, and pushes the particle out of equilibrium. This process can be described by tools provided to us by statistical mechanics, in particular we showed how the diffusion coefficient was derived from equipartition theorem and the molecular-kinetic concept of heat. The linear response theory for non-equilibrium systems describe systems slightly displaced from equilibrium, using the Fluctuation Displacement theorem to relate the response of the system to Brownian motion. Finally, the optical trap displays how Brownian motion counteracts the optical force of the laser ‘trapping’ the particle. This interplay results in mild displacements from equilibrium which can be modelled using the equations presented in the preceding section. :::

Bibliography

All references provided in ‘The Astrophysical Journal’ citation notation.

-

Lemons, D. S., & Gythiel, A. 1997, American Journal of Physics, 65, 1079

-

Einstein, A., Investigations on the theory of the Brownian movement (New York, Dover Publications, 1956)

-

Cecconi, F., Cencini, M., Falcioni, M., & Vulpiani, A. 2005, Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 15, 026102

-

Toda, M., Kubo, R., Kubo, R., et al. 1998, Statistical physics II Nonequilibrium statistical mechanics (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin / Heidelberg)

-

Callen, H. B., & Welton, T. A. 1951, Physical Review, 83, 34

-

Bettolo, M. U. M. 2008, Fluctuation - dissipation: Response theory in statistical physics (Amsterdam: Elsevier)

-

Kubo, R. 1986, Science, 233, 330

-

Pesce, G., Jones, P. H., Maragò, O. M., & Volpe, G. (2020). Optical tweezers: Theory and practice. The European Physical Journal Plus, 135(12). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-020-00843-5

-

E.F. Nichols, G.F. Hull, A preliminary communication on the pressure of heat and light radiation. Phys. Rev. 13, 307—320 (1901)

-

Ashkin, A. (1970). Acceleration and trapping of particles by radiation pressure. Physical Review Letters, 24(4), 156—159. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.24.156

-

Jones, P. H., Maragò Onofrio M., & Volpe, G. (2015). Optical tweezers: Principles and applications. Cambridge University Press.

-

Ashkin, A. (1992). Forces of a single-beam gradient laser trap on a dielectric sphere in the Ray Optics Regime. Biophysical Journal, 61(2), 569—582. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3495(92)81860-x