import scipy.integrate as integrate

import random

import math

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as npChapter 1

[!NOTE] The following chapter has been dutifully copied from the textbook, though into a style I prefer, sparsed in are some code blocks which you may collapse for readability purposes. Since this chapter is pivitol to understanding the rest of the work ahead - and has been written well by the author - I have been reluctant to make any large changes to the structure.

Chapter 1.1

1.1.1 Introduction

Monte Carlo Approximation of Integral:

is

Where , , are i.i.d random variables (remember that and are also r.v) that are uniformly distributed. An important point is that alpha is the mean of the integral of on interval and that .1

The key point here is that as , due to law of large numbers.

def f_x(x):

'''

This function returns the value of the function f(x) = x^2.

'''

return math.sin(x)

def integrator (func):

'''

This function integrates the function func over the interval [0, 1].

'''

return integrate.quad(func, 0, 1)[0]

def monte_carlo_integrator(func, n):

'''

This function estimates the integral of func over the interval [0, 1]

using the Monte Carlo method with n random samples.

'''

samples = []

for _ in range(n):

x = random.uniform(0,1)

samples.append(func(x))

return sum(samples) / n

exact_integral = integrator(f_x) #global variable to be used in variance calculation.

print("Exact integral of f(x) = sin(x) over [0, 1]:", exact_integral)

n_values = [10, 100, 1000, 10000]

for n in n_values:

mc_integral = monte_carlo_integrator(f_x, n)

print(f"Monte Carlo estimate with {n} samples: {mc_integral}")

print(f"Error: {abs(mc_integral - exact_integral)}")

Exact integral of f(x) = sin(x) over [0, 1]: 0.45969769413186023

Monte Carlo estimate with 10 samples: 0.4537232939319543

Error: 0.005974400199905916

Monte Carlo estimate with 100 samples: 0.4307030920247507

Error: 0.028994602107109524

Monte Carlo estimate with 1000 samples: 0.4692670118673434

Error: 0.00956931773548314

Monte Carlo estimate with 10000 samples: 0.4550396312741984

Error: 0.004658062857661849Since MC method uses random sampling from unifrom distributions, on some runs of the code above, n=10 may be more accurate than n=100 for the function x^2! This seems to happen less with the function sin(x).

Variance and Asymptotic Normality

We define the variance of the function over the interval as:

Since , we are interested in the variance of the random variable , where .

By the standard formula for variance:

This is equivalent to:

which expresses the same variance as a mean squared deviation from . 2

def sigma_squared(func, n):

'''

This function estimates the variance of the function func over the interval [0, 1].

'''

alpha = exact_integral

return integrate.quad(lambda x: (func(x) - alpha)**2, 0, 1)[0]

print("Variance of f(x) = sin(x) over [0, 1]:", sigma_squared(f_x, 10000))Variance of f(x) = sin(x) over [0, 1]: 0.0613536733034302Now consider the Monte Carlo estimate:

Because the are i.i.d., the values are also i.i.d. with mean and variance .

Therefore, the variance of the sample mean is:

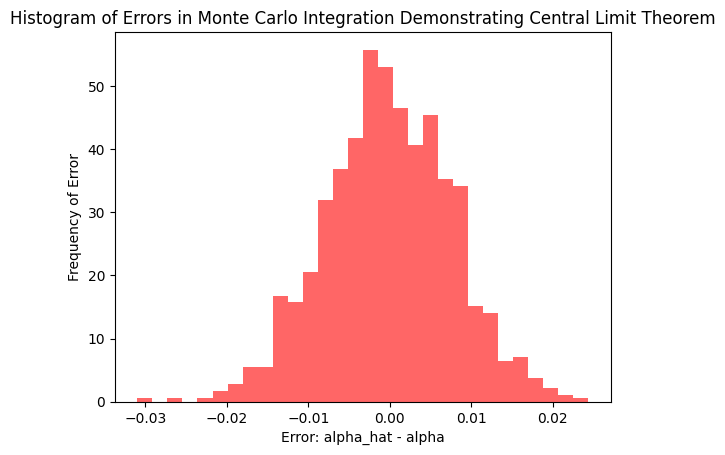

By the central limit theorem, as , the sampling distribution of becomes approximately normal:

This implies that the error term

is approximately normally distributed with:

- Mean:

- Standard deviation:

def error_term(func,mc_estimator,exact_integral,n):

return mc_estimator(func,n) - exact_integral

n = 1000

errorsList =[error_term(f_x,monte_carlo_integrator, exact_integral, n) for _ in range(1000)]

plt.xlabel('Error: alpha_hat - alpha')

plt.ylabel('Frequency of Error')

plt.title('Histogram of Errors in Monte Carlo Integration Demonstrating Central Limit Theorem')

plt.hist(errorsList, bins=30, density=True, alpha=0.6, color='r')

plt.savefig('histogram_MC_Integration_CLT.png', transparent=True)

plt.show()

print(f"Mean of errors: {np.mean(errorsList):.6f}")

print(f"Standard deviation of errors: {np.std(errorsList):.6f}")

print(f"Theoretical Standard Deviation: {math.sqrt(sigma_squared(f_x, n) / n):.6f}")

Mean of errors: -0.000182

Standard deviation of errors: 0.007798

Theoretical Standard Deviation: 0.007833In practice, is usually unknown because it depends on the unknown integral .

We approximate it using the sample variance of the observed values :

and the sample standard deviation is:

This gives us a way to estimate the uncertainty in the Monte Carlo approximation.

def sample_standard_deviation(func, n, monte_carlo_integrator):

'''

Calculate sample standard deviation using the formula from page 2.

'''

# Generate n samples

samples = [random.uniform(0, 1) for _ in range(n)]

# Calculate f(U_i) values

f_values = [func(u) for u in samples]

alpha_hat = monte_carlo_integrator(func, n)

squared_deviations = [(f_val - alpha_hat)**2 for f_val in f_values]

s_f = math.sqrt(sum(squared_deviations) / (n - 1))

return s_f

n=1000

print(f"Sample Standard Deviation: {sample_standard_deviation(f_x, n, monte_carlo_integrator)/ math.sqrt(n):.6f}") Sample Standard Deviation: 0.007941Why Monte Carlo?

For 1-dimensional twice-differentiable functions, the trapezoidal rule’s error rate is while the MC method’s error rate is . Hence, for low-dimensional integrals the MC method is not competitive.

MC method truely shines on larger dimensional integrals as the error rate stays while the trapezoidal rule has error rate (it decays with higher dimensions).

Modeling the value of a derivative secruity using MC requires simulating multiple stochastic paths (say, with Geometric Brownian Motion) that model the evolution of the underlying security, interest rates, model parameters, and other relevant factors. Instead of sampling from , we sample from a space of paths (which are all possible trajectories of the price of the underlying security). As stated in the textbook: “The dimension will ordinarily be at least as large as the number of time steps in the simulation, and this could easily be large enough to make the square-root convergence rate for Monte Carlo competitive with alternative methods.”

1.1.2 First Examples

- : Price of the stock at time .

- : Strike price; the fixed price at which the holder can buy the stock.

- : Expiry time; the fixed future time at which the option can be exercised.

- : Current time

Call option — A financial contract granting the right (not obligation) to buy a stock at price at time .3

The payoff to the holder at time is:

If , the option is exercised, and the holder profits: . If , the option expires worthless (no profit or loss).

We multiply by a discount factor , where r is a continuously compound interest rate. The expected present value is defined as .

- Note: This discount factor should feel familiar to any physicist. This is the same decay factor used in damped springs and radioactive decay. Its form comes from solving differential equations of the form . Discount factor is applied due to money being compounded with a factor of . i.e If you have dollars today, you could invest it risk-free and have dollars at time .

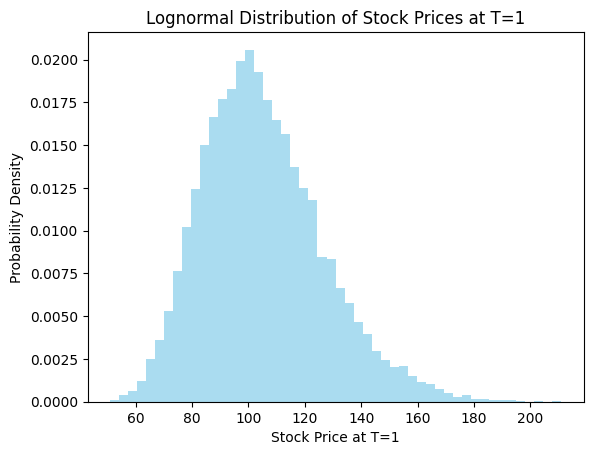

To describe the evolution of the stock prices we employ the Black-Scholes equation, a stochastic differential equation.

- is the volatility of the price of the underlying security.

- is the mean rate of return interest rate (through some measure theory (change in metric) I don’t quite understand). This equivalance implies risk-neutral dynamics.

- is standard Brownian motion.

We can interpret this by saying we find the percentage changes () as increments of Brownian motion.

The solution the SDE is:

at terminal time . W is normally distributed with mean and variance - which is the same as the distribution of where .

S0 = 100 # S(0)

r = 0.05 # risk-free rate

sigma = 0.2 # volatility

T = 1.0 # time to expiration

n_scenarios = 10000

def S_T (S0,r,sigma,T,n_scenarios):

# Generate n scenerios

# W(T) = sqrt(T) * Z, Z ~ N(0,1)

Z = np.random.normal(0, 1, n_scenarios)

W_T = np.sqrt(T) * Z

#Exact Soultion

S_T = S0 * np.exp((r - 0.5*sigma**2)*T + sigma*W_T)

return S_T

#Visualization

plt.hist(S_T (S0,r,sigma,T,n_scenarios), bins=50, density=True, alpha=0.7, color='skyblue')

plt.xlabel('Stock Price at T=1')

plt.ylabel('Probability Density')

plt.title('Lognormal Distribution of Stock Prices at T=1')

plt.savefig('lognormal_distribution.png', transparent=True)

plt.show()

print(f"Theoretical mean: {S0 * np.exp(r*T):.2f}")

print(f"Simulated mean: {np.mean(S_T):.2f}")

Theoretical mean: 105.13

Simulated mean: 105.13Footnotes

-

Here alpha is infact the same as .

Then

Where U is the uniform distribution on interval .

This makes the mean of f(x). ↩

-

We know

Next, add and subtract the cross‐term and add :

Thus,

confirming the equivalence. ↩

-

Specifically, these are European options. American options can be exercised at any time . ↩